Showing posts with label Richard Feynman. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Richard Feynman. Show all posts

Saturday, June 18, 2011

Decide for yourself

I say, give everyone a chance. Listen—or read—to them all, since we’re all of us monkeys on the same branch of the evolutionary tree. But heed or give more credence to those who speak more closely to your heart. In time, you’ll become more discerning. You’ll get to the point of being able to hear—first-hand, from your own mouth, in your own style—lessons that you already, miraculously, know. As the Chinese proverb goes, listen to what everyone has to tell you, but then decide for yourself.

According to Cato the Elder wise men learn more from fools than fools from the wise. Bruce Lee said that a wise man can learn more from a foolish question than a fool can learn from a wise answer. The flip side of this coin is just as important, however. Richard Feynman, winner of the Nobel Prize for his work on quantum electrodynamics, as a boy was told by his father never to have any respect whatsoever for authority. “Forget who said it and instead look at what he starts with, where he ends up, and ask yourself, ‘Is this reasonable?’”

Friday, June 10, 2011

Identity check

Because my style of thinking follows on from the type of person that I am, it may be useful if I divulge a little about my personality. That may help you to decide how much credence to give me. Words don’t exist in a vacuum; they are coloured by the character of their user. Consequently, there’s a reason for me to prove myself worthy. Whether I want to or not, I’m going to have to crawl out on that limb.

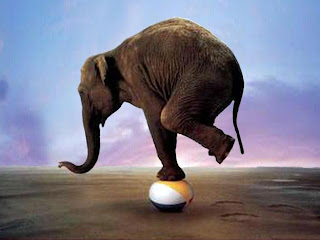

Though no man is an island, I keep myself a strictly-patrolled peninsula. By that, I mean that I’m semi-permeable to other input. Through reading I’ll happily incorporate ideas from external sources. But I do so very judiciously—and I’d recommend that you apply the same strategy. Tread cautiously. Do allow ideas from foreign sources to pollinate you, but don’t let yourself be genetically modified in the head. It’s a finely-tuned balancing act.

In No Ordinary Genius, David Goodstein tells of getting together with Richard Feynman one evening to read with excitement the manuscript of Jim Watson’s (and Crick’s) The Double Helix, a year before that milestone of a book was published.

“Watson must have been either very lucky or very smart,” remarked Goodstein to Fenman, “because he never knew what anybody else was doing, and yet he still made the crucial discovery.”

Replied Fenman, “That’s what I learned from reading it. I used to know it, and then I forgot it—I have to disregard everybody else, and then I can do my own work.” And so, given that Will? I Am! originated almost exclusively from me, the time might be right to reveal a little about myself (the bare minimum, I promise us both).

I always feel awkward when I’m asked who I am. The conventional response is to name an occupation, as if the activity that brings dollars through the door defines one as a person. Well, that isn't how I see myself. My day job is incidental to who, or what, I am. I place more emphasis on making a life than on making a living.

And yet I wouldn't feel comfortable coming out with the truth either—declaring for example that I’m a seeker. I hate it when people respond, “Whaaat!?” so I tend to 'um' and 'er'. To entrust a stranger or even an acquaintance with a deeper response, and for me to divulge how I relate to the universe, and what I deem to be important in my life, isn't for casual conversation.

It should suffice that English is my mother tongue, and that I can make myself understood. I write competently (if you can ignore my irrepressible wit). I don’t require that you trust me. I don’t care whether you relate to me or not. Both are irrelevant to me. I’ve grown up largely outside the influence of any major religion, so have no vested interest in any dogma or belief system. More than that, you don’t really need to bother yourself with.

Why wonder about whether I’m male or female (or combination thereof)? Surely my physical appearance—height, weight, skin colour and shoe-size—is of no consequence. I’m above the age of consent—of an age, in fact, to have grandchildren. It shouldn’t make a jot of difference whether I’m confined to a wheelchair, or run marathons. I have most of the ‘seven smarts’ and do well in intelligence tests, though have never felt that to be an advantage—the reverse, if anything. You ought not to care a hoot whether I have a steady job or am unemployed. Why would you give a fig about whether I write from a prison cell or via the free Internet access suite at the local library? What does it matter where I hang my hat?

Friday, May 27, 2011

Disbelief

Frankly, I don’t believe in anything. I don’t ‘believe’, full stop.

By definition, when you believe in something, you hold something to be true regardless of any contrary evidence. In fact, the stronger the evidence against your belief, the more tightly you clutch fast to it, as if this is some sort of test of faith. “Dumb, dumb and dumber,” say I.

Only a dope elects to close off her mind against any future change or growth. Why do so? Is it to stave off the discomfort of having to amend one’s worldview? Is it to hold at bay the unease of being uncertain? The Nobel Prize-winning scientist, Richard Feynman, a gentleman that I have a lot of time for, loved to be in a position of not knowing. It spurred him on in his inquiries and made life interesting for him.

To me, investing ‘faith’ in some authority figure’s story is nothing but a cop-out, I've always felt. The only thing that prepackaged philosophical narratives offer is a ready-made excuse not to think for oneself, but then you give up that power to some group, or to a theocracy.

So I will not ‘believe’. I won’t blindly accept any unsubstantiated proposition (which is not to say that I’m materially-minded, and that I limit my thinking to objects that I can sense, or that I confine myself to musing upon the mind-figments derived from logical and philosophical machinations). All I’m saying is that to kow-tow willy-nilly to any historical or mythological celebrity is not my scene. I don't swallow any particular line, and I don't expect you to swallow all that I say either.

But I do believe that you’ll find pearls of wisdom most anywhere. That said, here’s where I do my version of a literature review, and mention a few influences on my thinking. But before I do so, I’ll offer a word of warning.

It’s certainly true that I have benefited from reading what others have to say, but that has mostly been supplementary. Ultimately, I'm accountable to myself only. I must use the manner and style of thinking that suits me best. Just like Feynman, for the most part, I’ve felt it necessary to isolate myself from others' philosophies. I didn't want to risk being steered off track.

Sunday, April 24, 2011

Photon's perspective

What I mean to do next is to demolish time itself (Einstein, cheer me on!). What I suggest is that our spark doesn’t have to follow a particular sequence or order before returning to the here-and-now. I’m proposing that any point in time is as good as another. Every instant is real for the consciousness quantum spark. It may leap distances within the present or make temporal leaps (and in combination). It only needs to do so randomly. Eventually it will ‘hit’ that instant of consciousness next to where it was, and the two will feel linked. And believe it or not, that idea is not unfounded. It has some support.

Thomas B. Czerner, the author of What Makes You Tick? writes:

‘As they travel, photons have a mysteriously unified view of things. If they had taken a clock and an odometer with them on their trip from a distant star, the time and the distance travelled would have measured zero. At light speed, time stands still, distances collapse, and everything is in the here and now. From the perspective of the photon, everything along its path – the start from which it came and you – exist at one point, simultaneously, and since time stands still, eternally. As you travel at your leisurely pace you are oblivious of that extraordinary state of affairs. Eternity and total unity are physical entities that lie outside of your direct awareness.’

Additionally, the physicist Feynman (and his thesis advisor John Wheeler) came up with the equally astounding idea that the universe may actually be a single electron/positron leaping about all over the place both backwards and forwards in time so quickly that it ‘fills out’ the entire thing.

Wednesday, April 13, 2011

Alpha omega

Let’s work this model a little harder.

Okay, so a life form has access to a set of memories. We call the whole a life. And we know that memory awareness is like an arrow pointing back in time.

Now, each time moment contains within itself a nested subset, or the memory-awareness of other moments (imagine a Venn diagram with subsets that get smaller and smaller (perhaps an onion (that does not need to be of glass (or contain a walrus)))) then, within the context or paradigm of continuous expansion, growth or progress, this makes it seem that time flies forward. (Within a paradigm of shrinkage or disappearance it ought to result in the opposite: that time is progressing into the past.)

Similarly, you appear to be travelling along with it. The universe too—it seems to explode and then, after aeons, implodes back into its black hole. Whether it does so once, or else loops back on itself like a Moebius strip, or even if it oscillates repeatedly ad infinitum, doesn’t matter, since none of those cosmologies break free from the gravitational pull of the illusion of time.

Those models only seem to be kinetic, whereas from god’s point of view everything is. It is all here, complete, the alpha through to the omega. The alphabet exists as a unit. The letters don’t scroll in real time; they’re carved in stone.

All is as it is.

All particles are linked according to the laws of gravity, electromagnestism and so forth. They relate to one another as if they were separated in space and time, and though they each seem to be discrete, there is in fact no way to tell them apart.

All is indeed one.

Okay, so a life form has access to a set of memories. We call the whole a life. And we know that memory awareness is like an arrow pointing back in time.

Now, each time moment contains within itself a nested subset, or the memory-awareness of other moments (imagine a Venn diagram with subsets that get smaller and smaller (perhaps an onion (that does not need to be of glass (or contain a walrus)))) then, within the context or paradigm of continuous expansion, growth or progress, this makes it seem that time flies forward. (Within a paradigm of shrinkage or disappearance it ought to result in the opposite: that time is progressing into the past.)

Similarly, you appear to be travelling along with it. The universe too—it seems to explode and then, after aeons, implodes back into its black hole. Whether it does so once, or else loops back on itself like a Moebius strip, or even if it oscillates repeatedly ad infinitum, doesn’t matter, since none of those cosmologies break free from the gravitational pull of the illusion of time.

Those models only seem to be kinetic, whereas from god’s point of view everything is. It is all here, complete, the alpha through to the omega. The alphabet exists as a unit. The letters don’t scroll in real time; they’re carved in stone.

All is as it is.

All particles are linked according to the laws of gravity, electromagnestism and so forth. They relate to one another as if they were separated in space and time, and though they each seem to be discrete, there is in fact no way to tell them apart.

All is indeed one.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)